It’s a classic American scene: a herd of young children file into a classroom piling apple after apple onto the desk of Mister or Missus Teacher. The board reads American History, and upon the request of Mister or Missus teacher the cultish classroom erupts with the jingle, “Columbus sailed the ocean blue in 1492”. This number has been etched on blackboards, brushed on whiteboards, projection onto screens, and drilled into the heads of American children for centuries now. What has changed is the information that follows this chant, for it may be the only consistent fact taught to Americans over the last few centuries. Columbus was in fact a man, who took ships across the ocean, traditionally said water is automatically assigned the color blue, and landed somewhere in 1492. Some argue he knowingly landed in the Caribbean, while others say he died believing he found the eastern passage to Asia.

Overtime certain aspects of Columbus’ story has been altered to be more ‘factual’. For our purposes factual can be defined as what an historian is able to hypothesize upon the examination of available information and evidence. What was once ‘factual’ may now be considered entirely outlandish or absurd. To be entirely fair, it should be noted that this essay, and any perspective that may be presented within it, is based upon what is considered factual as of March 2018. The way Columbus’ story has been taught has changed ever since he first crossed the Atlantic. Upon the analysis of textbooks from 1823 to 2017, written by a variety of historians of various backgrounds, one is able to a trace the ever-changing legacy of Columbus; first as a hero, then as a victim, and finally most recently as a blood thirsty fool. This change in legacy can directly be connected not only to the changing ‘factual’ evidence being presented by these historians, but also by how they present it.

The first person to associate Columbus with being a hero was perhaps his biggest fan, Christopher Columbus himself. In a letter to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain in 1493, he wrote, “I know that you will have pleasure of the great victory which our Lord hath given me,” inferring that it was he who was so worthy as to receive such a gift. He then makes mention of his most heroic action of enslaving the native people of where he thought was India, for the goodness of Christianity. While looking at this from the view of a person in the 21st century this does appear to be absurd, his actions were heroic. Going back to the idea of ‘facts’, Christians of this time saw the existence of God not as a belief but as a ‘fact’. A devout Christian like Columbus could only ever make such a discovery if it were given to him by God. As a result, and as the letter clearly indicates, from the very beginning Columbus was seen as a hero sent to Earth by God. Later authors who wrote about Columbus would be caught up in the heroic legacy he left. As long as God remained a powerful presence in the lives of Americans, a level of justification was applied to the acts of violence and destruction he placed upon the Native people he called Indians.

Another prime example of how Christianity shaped the way Columbus was viewed is Reverend Charles Goodrich’s 1823 A History of the United States of America. His story of the United States started with its discovery in 1492, upon the arrival of Columbus. He made no mention of the people who had been there for thousands of years, beyond referring to them as primitive. One can assume that being a religious man himself, Goodrich agreed that God did not object to the enslavement of the pagan Natives. Goodrich also stated that “Columbus was doubtless entitled to the honour of giving a name to the New World. But of this honour he was robbed” (Goodrich 8), establishing Columbus as a victim. He argued that it was Columbus who was the founder of the new world, and it was tragic that the land would be known as the Americas and not by his name. Like many others, he also mentions how Columbus was arrested and died powerless. Goodrich cited the jealously of others as the reason for this fate. The reading is short but very quickly establishes the author to be a fan of Columbus even though he lacked citation. The root of his information was limited and as a result, the accuracy of his account should be questioned. On the other hand, this history allows readers to see how in the 1820s Columbus was being looked at as a tragic hero.

Columbus’ legacy would not change much by 1856 when Emma Willard of Connecticut wrote how she interpreted his story. Willard, like Goodrich, credited Columbus with the founding of a New World and described him as being “sent home in chains, from the world which his genius had given the Spanish Monarchy” (Willard 11). Willard’s piece established that American history began with the arrival of Columbus, titling the chapter “Part 1, Period 1, Chapter 1,” and mention of the inhabitants prior to the spread of Columbus’ genius is virtually nonexistent.

The mention of Isabella’s vital role as the determined facilitator of the trip, even willing to give up her jewels to see it come to fruition, in juxtaposition to the mention of the “ingratitude of Ferdinand” (Willard 11), is now known to be inaccurate; however, what it says about the point-of-view of the female author and the 1850s is vital. Willard delivers the story of Columbus from the perspective of a woman historian, in a time when men dominated the field, and speaks heavily to the political climate of the women’s movement that had gained ground with the Seneca Falls convention just eight years prior. If you were to read Alan Taylor’s 2001 American Colonies, the mention of Isabella’s willingness to sacrifice her jewels for the founding of the New World would be nonexistent. Willard mentioning this detail, which would have been passed as ‘factual’ to readers, may have been a progressive political stunt, leading to the spread of incorrect information. Willard offered a similar view as Goodrich in the sense that she viewed Columbus as a victimized hero; however, her lack of citation and inclusion of politically charged and unsupported detail, provides us with a better description of the view of Columbus’ story in the 1850s than perhaps the actual truth behind the story itself.

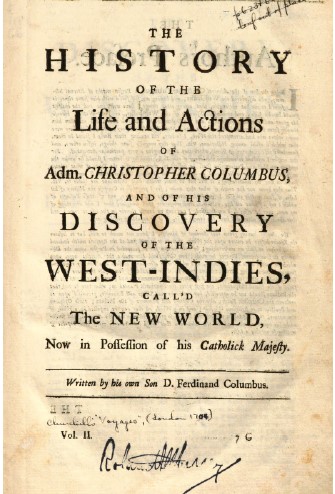

From the 1880s to the late 1910s the histories of Columbus experienced a major transition from the histories previously discussed. Historians such as Thomas Higginson, author of the 1883 History of the United States, and Dr. David Muzzey, author of the 1917 An American History, described Columbus’ story in far greater detail. Each author spent time explaining details leading up to to Columbus’ journey, such as the closing of the eastern passage to Asia and Eastern expansion onto the islands off the coast of Africa. Another major ‘factual’ detail both authors included was Columbus going against the common idea that the earth was flat, searching for an eastern passage to Asia, not a New World. Higginson mentioned, “Columbus studied such maps, or helped to draw them, and grew more and more convinced, that, if he could only cross the unknown ocean, he would find India on the other side” (Higginson 33), while Muzzey established that Columbus “shared with the best scholars of his day the long established belief in the sphericity of the earth” (Muzzey 5). These men marketed Columbus not as a hero because he went on a journey for a New World, but because he was smart enough to know that the earth was round. While he was still being seen as a hero, these authors began to turn towards the idea that the discovery was accidental. In regards to the truth behind whether or not Columbus was actually a genius for knowing the earth was round, historians today generally believe that this was widespread knowledge of the 1490s. This was not the case in the time of Higginson and Muzzey who believed it to be ‘factual’ that it took a genius to know the earth is round. Perhaps this is because a source cited in Muzzey’s work was Ferdinand Columbus’ biography of his father Christopher (Muzzey 5), one of which was filled with praise and admiration.

Finally, Higginson felt that injustice was served upon Columbus by naming the new world the Americas because he, like Goodrich and Willard, believed Columbus was aware that he found a New World. Muzzey’s 1917 history was much more accurate to what we know as true today in the sense that it stated Columbus had died thinking he found “a new way to the Old World” (Muzzey 13). This was another step towards understanding Columbus to have discovered the New World on accident; however, he was still seen as a hero for his bravery. From here on out, Columbus was no longer seen as just a mistreated hero who found a New World, but now was seen as a mistreated hero who accidentally found a New World (and maybe didn’t even know).

By 1956, Columbus had been established to be “one of the most successful failures of history” (Bailey 7) in Thomas Bailey’s The American Pageant. Given barely a page and a half, Columbus appeared 7 pages in, after Bailey explained the “moslim infidel” cutting off trade to the east and how technological advancement had made Columbus’ journey possible. Columbus was not credited as a hero or a genius, but rather he was described as clueless of what he discovered. Bailey mentioned how Columbus even called the Native Americans “Indians” because he believed that he was in India. The heroic role of Isabella mentioned by Willard was ignored, the never ending contemplation on the shape of the earth described by Higginson and Muzzey went unrecognized, and Columbus was in no way described as wronged because the New World was named America, because he had no idea where he was. As the 2017 Global Americans: A History of The United States demonstrates, modern thought agrees that Columbus only found the New World by accident.

Perhaps Bailey was able to draw these conclusions easier than the earlier historians because resources of the 1950s might provide more accurate information. While Bailey’s account did establish Columbus as mistaken, he took things a step further by almost entirely discrediting Columbus with any sort of real contribution, unlike the 2017 textbook that states Columbus did in fact jumpstart further exploration of the New world, whether it was on purpose or not. This could reflect 1950s anti-immigration sentiment looking to discredit any Spanish, Portuguese, or Italians from having any part in the founding of the nation. It should also be noted that it would not be until much later that any history of the Americas before Columbus would be written. The 2017 textbook dedicated forty-three pages to describing the world leading up to Columbus, therefore allowing the reader to better understand the circumstances surrounding the events that would unfold. From 1956 until present day, Columbus has been transformed from a victimized hero to a simple lucky fool.

Looking back at these histories today, Americans may have a tendency to laugh at the ‘facts’ being presented. Many may ask, why is it that so many educated people called Columbus a hero? Why is it that even today, students are brainwashed to memorize the haunting chant of the year in which Columbus got lucky? And why is it that it wasn’t until recently that the negative effects of Columbus have been discussed? As mentioned in the beginning, what is defined as ‘factual’ is ever changing. As new things are discovered, and new perspectives emerge, what was once fact may very well become known as fiction. Common belief at one point said that Columbus was a genius for knowing the earth was round, but current evidence points out that this was common knowledge of the period. Isabella was established to be a feminine hero do to the fact that Emma Willard could not withstand establishing a powerful female figure, because perspective made her susceptible to developing what is now thought to be a false.

Many people argue that Columbus Day should not exist because modern opinion favors the fact that Columbus had made a mistake which led to the murder of millions of Native Americans. Perhaps rather that eradicate it, we should use Columbus Day to revisit the modern thought of Columbus’ story. What Columbus Day meant for Muzzey or Bailey and what it will mean for people in 2042 may be entirely different, but the dialogue that arises from it is equally valuable. The legacy of Columbus and the way his history is presented may change as ‘factual’ evidence mixes with modern perspective, but the the importance of seeing Columbus change from a hero, to a victim, to a fool, and to whatever he becomes in the future, is important to demonstrating a growing and evolving society.

Works Cited

Visit our page on the textbooks used in the course of our contributors’ research and writing.