Historical descriptions of people and events have changed vastly over time. Looking at a guy like Christopher Columbus (my analysis of historians’ relationship with him can be seen here), an important figure in the American historical canon despite his lack of connection to the present day United States, there was a clear shift from historians praising Columbus for his accomplishments and pitying him for his shortcomings to providing a more critical analysis. Realizing the initial upbeat reaction to an explorer who had little connections to actual American culture, I wondered if the reaction would be similar for someone who fit the same description but was more connected to what became the United States. John Smith made sense here, and after looking at many of the same texts that I used earlier, the same pattern was seen: initial praise and focus on the explorer’s life that slowly morphed into a critical analysis more concentrated on the events rather than the man. As noted above, other than exploring for a living, the two had little in common. Columbus was Italian who sailed under the Spanish flag in search of gold and explored the Caribbean and Central America without knowing where he was going. Smith was an Englishman tasked with leading a group of lazy, troublesome men to North America so he could establish an economic base for the his home country. So why did early American historians fall so in love with their stories? Given the time period, it is safe to assume their anti-Indian sentiments shaped their writings, and as relations between Americans and Natives became friendlier, historical analysis of Smith and Columbus became more neutral. The refinement of practices by historians also played a part.

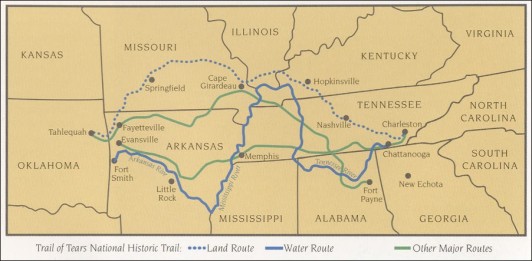

The first two texts about John Smith contain the most anti-Native perspective, and as a result the most Smith focus and praise. The earliest text, A History of the United States of America by Rev. Charles A. Goodrich, was written in 1823. This text gave five pages of an incredibly extensive history of Smith’s upbringing and adventures before even discussing what he accomplished in North America. Here, Goodrich described Smith as having great “courage and genius” (Goodrich 19). It would not surprise me if he used these exact words to describe Columbus (he does, in fact, call Columbus a genius on page 10 of the same textbook). He then goes on to describe the Pocahontas story, giving only the version Smith told, during which Pocahontas ran up to him and laid down on his body as Powhatan was about to execute him. He did not acknowledge any objectives by the Native American people about this story’s legitimacy. During his description, he used derogatory words such as “savages” when referring to the Indians and described Powhatan as “weak” (Goodrich 19). From today’s perspective, it appears Goodrich is not even attempting to hide his contempt for Natives. But at the time this was written, I doubt anyone even batted an eye. The hate for Indians was intense in 1823, with battles on the frontier. Only seven years after this was written, Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law, pushing the Natives out of their homes in the South and into reservations, creating the infamous Trail of Tears. Natives, still looking to fight for their land, clashed with American forces, so many Americans thought of Indians as the enemy. Imperialism and race-based hatred were behind the anti-Indian perspectives and policies.

Emma Willard’s History of the United States, written in 1856, contained many of the elements seen in Goodrich’s history. While not focusing as much on Smith’s history before coming to America (either a sign of his diminishing importance, or just a stylistic decision by Willard), she dug much deeper into the Pocahontas story than he does, only acknowledging Smith’s version. This was seen both in Willard and Goodrich’s versions, and it is significant because it shows how the word of the white, European man was valued over the word of the Natives. She also sung praises for Smith the man, describing him as energetic and cheerful in what otherwise was a volatile situation (Willard 22). When describing Smith’s capture by Powhatan and his warriors, she said he “found himself hunted by swarms of savages” (Willard 22), using the same derogatory term that Goodrich used. Willard’s language linked to the idea of the manifest destiny and the continued pushing of the Indians further and further west until they had nowhere to go.

Starting with Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s Young Folks’ History of the United States in 1883, writings about John Smith became less about the man himself and the Pocahontas story and more about Smith’s role in the Jamestown colony. More praise was seen about Smith’s work in the Jamestown colony than praise about his personality traits, a change of pace from the previous two authors. Higginson mentioned Smith’s methods of punishment (for example, pouring cold water down ones sleeve for cursing) and appreciates his accomplishments, saying, “He himself worked harder than anybody” (Higginson 114). Higginson is also the first author to mention skepticism behind Smith’s Pocahontas story, noting, “This story has been doubted in later times” (Higginson 115-116). He put enough trust in the Indians’ account to include it in his American history, a significant step forward towards viewing the Natives as equals. Another large step forward was in Higginson’s use of language, as he did not refer to the Natives by any derogatory terms. By 1886 Americans had reached the Pacific Ocean and would turn to imperialism beyond the North American continent. By then, America perceived immigration issues as pressing (for example, passing the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882), shifting the spotlight away from the Indians.

Similar themes continued in David Muzzey’s An American History (1917) and Thomas Bailey’s The American Pageant (1956). Both authors only included about a paragraph about Smith, a stark contrast from the ten-or-so pages seen in earlier books. Muzzey did not even mention the Pocahontas story, while Bailey did, but acknowledged doubts about its authenticity, stating, “The dusky Indian maiden Pocahontas may not have saved the captured Smith’s life, as he dramatically relates” (Bailey 14). Muzzey and Bailey both praised Smith for the work he did in Jamestown, as Wentworth did. Muzzey called Smith’s efforts “almost superhuman” (Muzzey 29) and Bailey said Smith was resourceful and a good leader (Bailey 14). While praise was still thrown Smith’s way, it had a tone of respect rather than admiration. By the 20th century, fighting with the Indians had stopped, as Americans looked beyond the North American continent to pursue more global interests. Heavy immigration from southern and eastern Europe along with two World Wars pitted the United States against new enemies.

The most recent account of John Smith gives us the most neutral and objective analysis yet. In his piece about Smith in American Colonies (2001), author Alan Taylor removes his voice almost completely, identifying Smith’s importance in colonial history but not singing his praises at all. Taylor offers a new explanation of the Pocahontas tale, saying that a misunderstanding led to Smith thinking he was going to be executed when Powhatan was only staging a ritual ceremony (Taylor 123), showing how the situation was viewed from both the Indian and European perspectives. Taylor also details the growing professionalism and objectiveness in the taking of history that has developed by the time he wrote his book in his intro. He notes the importance of telling the entire story and speaking from multiple perspectives as opposed to telling history from a solely-American perspective, which is seen in Goodrich’s and Willard’s texts.

Just like everything, how history is told has changed over time, and will continue to do so. Looking back, Goodrich and Willard appeared to view Indians in the same light as explorers like John Smith and Christopher Columbus did – roadblocks in the way of power and prestige. Additionally, the recording and analysis of historical events was relatively new, so there were not really any guidelines or practices for historians to follow. As the art of the historian became more refined, along with the goals of the United States of America, how the history of Smith, Columbus, and other imperial explorers became more of a critical analysis than a drawn-out compliment.

Works Cited

Visit our page on the textbooks used in the course of our contributors’ research and writing.

“John Smith: Images gallery.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/biography/John-Smith-British-explorer/images-videos.

Trail of Tears Map NPS. “Trail of Tears.” Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trail_of_tears_map_NPS.jpg. Accessed 3 May 2018.

1 Comment